Organisers: Adam Cieśliński, Agnieszka Tomas (Faculty of Archaeology, University of Warsaw, Poland), Chiara Cenati (Institut für Alte Geschichte und Altertumskunde, Papyrologie und Epigraphik, University of Vienna, Austria)

Organisers: Adam Cieśliński, Agnieszka Tomas (Faculty of Archaeology, University of Warsaw, Poland), Chiara Cenati (Institut für Alte Geschichte und Altertumskunde, Papyrologie und Epigraphik, University of Vienna, Austria)

Session format: in-person

Session language: English

Date: 19.03.2024 (Tuesday)

Place: Building of the Faculty of Archaeology UW, Warsaw, room 2.10

The contacts of the Romans with peoples living in lands beyond the frontiers of the Empire can be understood multidimensionally: through direct interactions but also in terms of the flow of ideas or goods. The aim of the proposed session is to present this issue from two archaeological perspectives: that of the Roman frontier provinces as well as that of the lands of the Barbaricum. The identification and understanding of the main categories of cultural relationships and interactions of a military, diplomatic and commercial nature is an important issue.

“The Roman perspective” has for many years been largely dominated by the narrative of written sources. The juxtaposition of this narrative with archaeological evidence provides an extremely interesting insight into the wider nature of these relationships – not only in the form of military conflicts or the image of “barbarians” in Roman art, but also through the presence and production in the provinces of elements of material culture characteristic of barbarian tribes, as well as changes and processes in the material and spiritual culture of Late Antiquity.

In the study of the ‘barbarian perspective’, it seems necessary to better understand the mechanisms of the displacement of objects of Roman provenance beyond the frontiers of the Empire, the role of local elites in their distribution, provincial influences on immaterial culture (religion, symbolism, habits), as well as issues related to the transfer of technology.

The aim of this session is to attempt to juxtapose these two perspectives, to compare research methodologies and to take a multidimensional view of the links between the Roman and barbarian worlds.

The detailed session program can be found here.

Abstracts:

Dávid Bartus (Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary)

“Quadorum venere legati” – The Emperor’s Fatal Meeting with the Barbarians in Brigetio

The legionary fortress is the least researched of the three main topographical parts of Brigetio. Although the retentura of the legionary fortress is almost entirely covered by modern buildings, the praetentura can be researched by remote sensing methods. The northern wall and gate, several roads and buildings have been identified on aerial photos during the last decades. One of the most interesting features is a large, apsidal building near the porta principalis dextra, which we excavated in 2017‒2018.

The area of the building is approximately 600 m2, consisting of an apse, two large halls and a number of smaller rooms. Several brick stamps and coins indicate that it was built most likely by the Frigeridus dux in the first years of the 370s. Valentinian I died on 17 November 375 in the legionary fortress of Brigetio, when he gave an audience to the Quadi and suffered a stroke, as told by Ammianus Marcellinus, but the exact location of the audience and the death of the Emperor was unknown until now. The aula-like plan and the dating of the building indicate that it was the most suitable place for an imperial audience, and Valentinian I most likely died there.

Ivan Bogdanović, Ilija Mikić (Institute of Archaeology, Belgrade, Republic of Serbia), Nataša Šarkić (Aita Bioarchaeology, Barcelona, Spain)

Hand in Hand to eternity: A Particular late Roman Triple Grave from Viminacium

Viminacium was a legionary fortress on the Danube. The capital of the Roman province of Moesia Superior, later Moesia Prima, developed alongside the fortress. As the so-called “city of the dead“, Viminacium is also the largest Roman cemetery ever excavated. In its broader vicinity around 14,500 graves were found.

The subject of this article is a unique burial, a triple grave (no. 60) excavated within the amphitheatre, situated in the north-eastern corner of the city. It is a portion of the tiny cemetery that has 67 inhumations dated to the late 4th century. Three men were discovered holding hands inside the modest pit. An anthropological investigation concludes that the individuals buried were most likely soldiers who were slaughtered mercilessly.

This paper serves as an introduction to the tale of the unknown soldiers and the community buried above the amphitheatre. We will also discuss the Viminacium in Late Antiquity when the city walls were dismantled and the amphitheatre was no longer in use.

Chiara Cenati (Institut für Alte Geschichte und Altertumskunde, Papyrologie und Epigraphik, University of Vienna, Austria), Florian Matei-Popescu (Vasile Pârvan Institute of Archaeology, Bucharest, Romania)

From Dacici Maximi to Carpici Maximi and Gothici Maximi: Wars and Victories on the Lower Danube in the Imperial Cognomina

Starting from the third century crisis, cognomina ex virtute referring to military victories became an integrating part of the imperial titulature. In a time of invasions, when the borders of the empire were severely threatened, especially on the Lower Danube, as we also learn from the new fragments of P. Herennius Dexippus’ Scythica (F. Mitthof, G. Martin, J. Grusková, Empire in Crisis: Gothic Invasions and Roman Historiography, Vienna 2020), this type of imperial propaganda had aim at being reassuring and represented a power statement by the emperors. In the third century AD, the title Dacicus Maximus appears in the official titulature of Maximinus Thrax (S. Nemeti, Dacici Maximi. The “Barracks Emperors” and the Conflicts with the Barbarians near the Frontiers of Dacia”, AMN 57/1 (2020) 129–141). Philippus Arabs is the first who adopts the cognomina Carpicus Maximus, followed by Aurelian and the Tetrarchs. In the late fourth century, the long lists of victories against barbarian tribes starts being summarized in expressions like debellator et victor gentium barbararum, which reflect the style and language of the Imperial Panegyrici (N. Zugravu, Veterum principum exempla superare. Un motiv retoric și ideologic în epigrafia, istoriografia și oratoria latină târzie, Classica et Christiana 17.1, (2022) 309–335).

In this paper, we shall give an overview on the use of these titles, with a particular attention to the meaning of Carpicus Maximus and Gothicus Maximus, which refer to the conflicts in the Lower Danube. How do these imperial cognomina evolve and how precisely do they refer to actual wars and victories? In what cases do they contradict the evidence of literary sources and archaeological finds or are supported by them? In what measure are they merely a result of imperial propaganda?

Adam Cieśliński (Faculty of Archaeology, University of Warsaw, Poland), Morten Hegewisch (Institute of Prehistoric Archaeology, Free University of Berlin, Germany)

A ceramic lamp from Turza Wielka (formerly Groß Tauersee) in north-east Poland. On Roman influences on the Barbaricum and the interpretation of selected adaptations

The paper presents the old find of a grave item from Turza Wielka. The find is a ceramic object that imitates a Roman oil lamp. The find has so far remained relatively unnoticed in research, but is being analyzed more intensively here. The grave context, cultural position and dating are highlighted, and possible Roman parallels are highlighted. To interpret the imitated oil lamp, the use of oil lamps in the Roman Empire is examined, and theoretical concepts are also used to interpret the lamp in the present findings.

Sven Conrad (University of Tubingen, Germany)

Roman finds on the left bank of the lower Danube – evidence of intensive contacts across the Limes border

During field surveys conducted in the year 2000 between Giurgiu and Zimnicea, Roman finds, mainly pottery, were discovered on several sites along the edge of the terrace. These finds can be dated to the 3rd to 4th century. As there have been no archaeological excavations to date, their interpretation is only possible from the context of other finds. The archaeological evidence suggests that these settlements in question were likely inhabited by the local population, as opposed to being provincial Roman sites. This is supported by the presence of finds that could be considered ‘Latest Iron Age’, the lack of typical Roman artifacts such as roof tiles, and the location of the sites themselves. These settlements can be attributed to the Sântana de Mureş-Chernyakhov culture, which is known for having a significant proportion of Roman artifacts in their graves and other archaeological features.

Katarzyna Czarnecka (State Archaeological Museum in Warsaw, Poland)

Why they didn’t like Roman locks and keys? Rare imports of locking devises from the Empire

Many various artifacts – coins, glass beads, brooches, swords, bronze, glass, terra sigillata vessels – were imported from the Roman Empire by the local people in Barbaricum. It is interesting why Roman caskets and keys very rarely appeared in the area outside the limes and in the area of the Przeworsk culture they are unique finds. The very first idea of the technique of producing locks was probably borrowed from the Celts, but the locking devices of caskets were an original, local invention. Separate finds of Roman keys (without lock elements) most probably should be treated as artifacts of special meaning (amulets?).

Roman padlocks also are extremely rare finds outside the limes. One of the most interesting find is a shackle padlock with a key from cemetery of the Bogaczewo culture in Mojtyny, north-eastern Poland. Apart from the very few, obvious imports from the empire (like discussed above find from Mojtyny), slightly different types of padlocks were in use in Barbaricum. The very principle of operation of the padlock is undoubtedly taken from Roman products, however, it had been creatively adapted by the local, Germanic locksmith.

Lina Diers (Austrian Archaeological Institute, Austrian Academy of Sciences, Austria)

Between and Beyond? Commodities and supply systems of the pottery production sites in the territory of Nicopolis ad Istrum (2nd–3rd c. AD) ‒ an overview

It has long been common consensus in the research debate about Roman Moesia Inferior/Thracia that the pottery production centres in the territory of Nicopolis ad Istrum supplied not only the main urban settlements but also the wider region between the Stara Planina and the Danube on a north-south, and the Osam and Yantra rivers on a west-east axis throughout the 2nd and 3rd century AD. A research project that is currently being conducted at the Austrian Archaeological Institute in Vienna now for the first time aims to verify this assumption with an encompassing approach and on a larger scale: A broad database of Moesian sigillata, red slip ware, utility ware, and cooking ware from the 4 main production sites of Varbovski Livadi, Pavlikeni, Butovo, and Hotnitsa as well as from the 2 urban centres of the region, Nicopolis ad Istrum and Novae, and 4 rural settlements of varying character – Kozlovets, Lyaskovets, Radanovo, and Gorna Lipnitsa/Mramora allows for the establishment of ware and fabric groups and the identification of potential spatial and/or chronological variations in the typology/production spectrum of the workshop sites. Archaeometric analyses (thin-section petrography and Instrumental Neutron Activation Analysis) add the level of provenance studies, which not only facilitates the determination of geochemical production fingerprints but also verifies the distribution patterns of the pottery throughout the area of interest. The presentation shortly introduces the project agenda and methodology and then zooms in on first results from the 2023 pottery campaign in Veliko Tarnovo and Svishtov.

Ireneusz Jakubczyk (Faculty of Archaeology, University of Warsaw, Poland)

Situlae E 18 in Barbaricum

Numerous objects from the provinces of the Roman Empire have been found and registered on Polish territory for more than two hundred years. These finds are referred to as Roman imports, very important and valued by archaeologists and historians historical sources. They are used to reconstruct the contacts of Barbarian peoples with the Empire, both of a commercial and political nature. In this group of finds, metal vessels, including buckets of the Eggers 18 type, occupy an honorable place. These vessels have already been analyzed many times in the literature. These studies have dealt with typological issues, the places of their manufacture, dating. To a lesser extent, these analyses have dealt with the context of their discovery and the accompanying artifacts. It is mainly on these elements that I would like to focus in the proposed paper.

Jan Jílek (Faculty of Arts, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic)

The cult of Iupiter Dolichenus in the Central European Barbaricum?

The study evaluates and interprets a new find of fragments of a triangular votive plaque of Iupiter Dolichenus from Újezd u Rosic, Brno-Country District (Moravia, Czech Republic) and places it in the context of the Central European Barbaricum and the Roman Middle Danube region. Due to their isolated occurrence in the landscape, the fragments of the triangular votive plaque from Újezd u Rosic are an evidence for ritual behaviour of the local barbarian populations rather than a lost item. The presence of the plaque outside the Roman border can hypothetically be connected with the events of the Marcomannic Wars, or with the period of unrest between the Germanic tribes and the Roman power under the Late Severans.

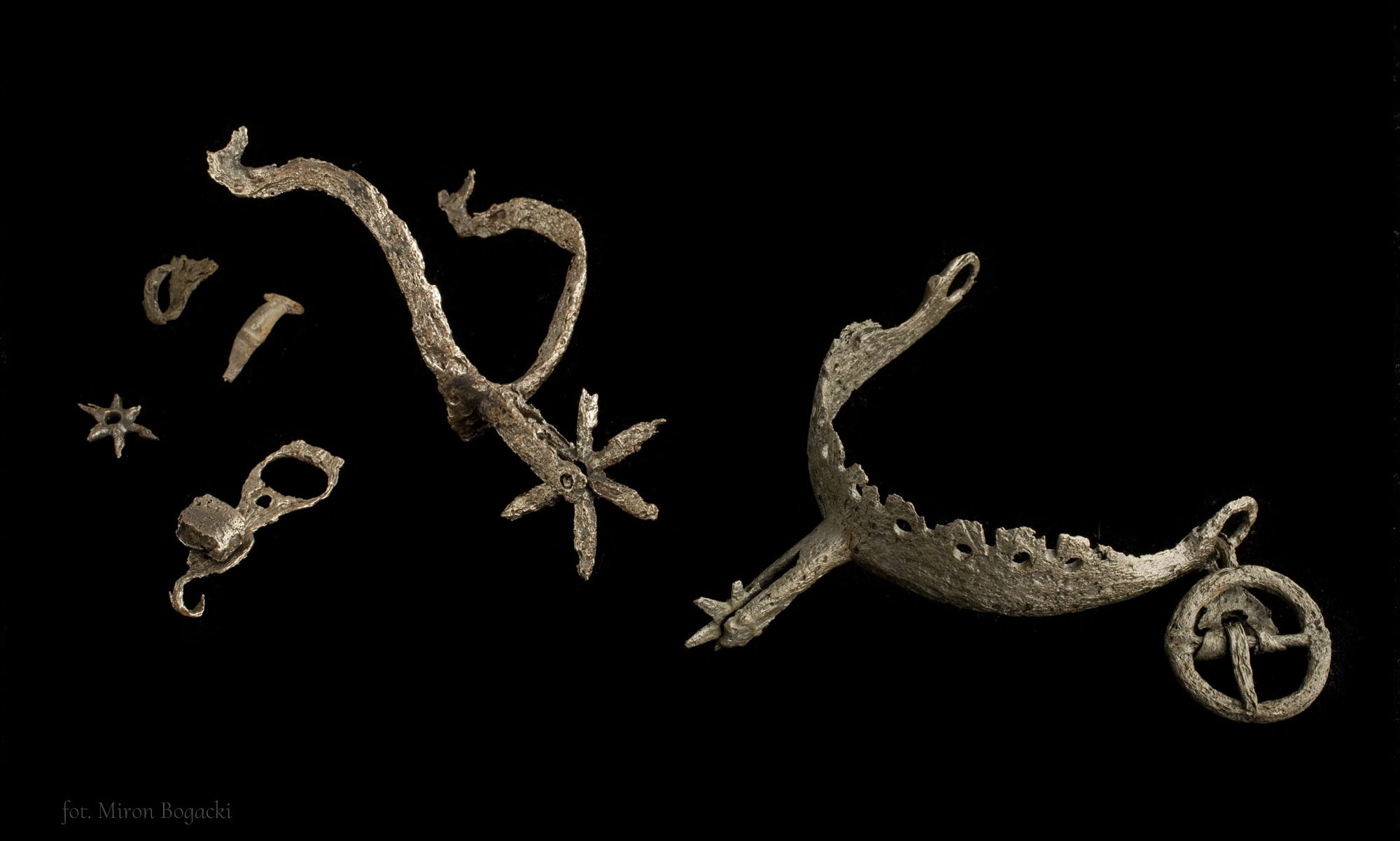

Bartosz Kontny (Faculty of Archaeology, University of Warsaw, Poland)

Turbulent time. Crisis of the Third Century as seen from Central-European perspective

New discoveries and studies shed a light on the cultural situation in the Central European Barbaricum in the third century. From one side one may observe militarisation and martial activity in northern Europe shown by war booty offerings (e.g. Illerup), from the other in spread of Scandinavian military model in Barbaricum, possibly resulting from the participation of Barbarians living to the south of the Baltic Sea in aforementioned wars and other military expeditions of ethnically mixed retinues. Finds from the battlefield at the Harzhorn in Lower Saxony (probably AD 235) allow to assume the participation of distant Barbarians in the clashes and so do the finds of Barbarian militaria found in destruction layers on the Roman limes. The catalyst for change may have been the presence of the Romans in Central Germany and Central Poland (Kuyavia), probably for the purpose of recruiting into the army. It led to the creation of a new cultural situation in the western Germania. Warriors from the Lubusz Group or Przeworsk Culture played their role in these affairs.

Martin Lemke (Faculty of Archaeology, University of Warsaw, Poland)

Your province is my pasture. The Dobruja in Antiquity in the eyes of Romans and non-Romans

Dobruja essentially comprises the Late Roman province of Scythia minor and ranges from Dunavăţi in the northeast and Smârdan in the northwest to the mouth of the Batova River on the Black Sea in the south. Geologically, it is in a sense a bridge: an extension of the South-Russian steppes meeting an extension of the Balkan foothills. It is also an area with a very specific landscape and climate, both modified only slightly over the last two millennia. Ovid described Dobruja as a treeless steppe and nearly 2000 years later General von Moltke wrote bluntly: “This land is a desert one would not expect in Europe”. Despite relatively fertile loess cover, Dobruja’s agricultural potential was rather limited historically, because of limited access to water. The population therefore was frequently nomadic, originating from the steppes of Scythia.

Rome was reluctant to include the area into the Empire, but once this was done on the basis of geopolitical necessity (securing the Danube frontier), the low population numbers in Scythia minor/Dobruja led the Roman administration to establish artificial settlements, easily discernible by the symmetry in their distribution and the Latin toponyms. This development program resulted in a relatively large number of agricultural communities in the Dobruja contrasting with their absence in other parts of Lower Moesia.

Dobruja’s role as a bridge for communication within this part of Europe was significant for the inhabitants on either side of the limes. If the Balkans are a link between Europe and Asia (Minor), then Dobruja is a bridge between the Balkans and the steppes of Ukraine and northeastern Europe. A road led along the eastern edge of the Balkan Peninsula, across Dobruja, through the least mountainous areas, connecting the Bosporus and northern Europe. Eventually, this geographical element, which may not have been very important for the inhabitants of the Mediterranean, became, starting in the 3rd century CE and in combination with convenient natural routes leading along the Prut and Dniester rivers further north, a catalyst for population movements that in effect turned the Roman world upside down.

The unfavorable “living” conditions in Dobruja were therefore naturally contrasted with the good transport conditions across the Balkans. Both factors were to have a dominant influence not only on the development of the province, but also, quite directly, on the history of the Empire.

Kyrylo Myzgin (Faculty of Archaeology, University of Warsaw, Poland)

Sworn friends, best enemies. Some new data on Roman-Barbarian relations in the light of the coin finds

Traditionally, the primary sources of Roman coins for the barbarian population are considered to be their military and political relations with the Roman Empire. These sources include plunder during military campaigns in the provinces, ransoms of prisoners, contributions, annual payments, diplomatic gifts, and payments for service in the Roman army. The economic role in the influx of coins, if any, was minimal and likely pertained mostly to territories bordering the Empire. Recent coin finds, particularly in Eastern Europe, indicate that in the second half of the 3rd and 4th centuries, a significant source may have been incorporating individual Gothic units into the armies of political opponents of the central imperial power. An overwhelming Gothic victory at Abritus in 251 probably established them as a formidable military force that the Empire had to consider. Furthermore, in the second half of the 3rd century, from the territory of the Roman provinces in the barbarian environment, the technology of counterfeiting official Roman coins may have penetrated. The presentation will delve into these and other new findings regarding Roman-Barbarian relations in Barbaricum during the Late Roman period in the light of the coin finds.

Andreas Rau (Leibniz Zentrum für Archäologie, Zentrum für Baltische und Skandinavische Archäologie, Schleswig, Germany)

Late Roman silver coinage in Northern Europe and Anglo-Saxon migrations

During the last two decades increased and professionalised use of metal detectors has led to an extreme growth in the number of siliquae/argentei in northern Germany and southern Scandinavia. Due to their very small number, these have so far been rather marginalised in the discussion of Roman coins in northern Europe, which is dominated by finds of denarii and gold coinage.

Both the composition of the material according to types and mints and the comparison with neighbouring regions allow important cultural-historical conclusions to be drawn. Furthermore, the occurrence of siliquae/argentei in burials and hoards of Hacksilber allow further interpretations.

These are particularly relevant to the question of the “adventus Saxonum” in Britannia, but also to the connection of this island province’s post/sub-Roman phase to the continent.

Melinda Szabó (Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary)

Women on the Barbarian border. A case study on the area of Brigetio

Living on the frontier of two words always has its own characteristics. In the specific situation of Brigetio (Komárom, HU), because of the legionary fortress and smaller forts, the most determining phenomenon on the Roman – Barbarian border was the dominance of military presence.

The question of my paper is the situation of women in these particular conditions. From Brigetio, 113 women are known, who were mostly members of soldier families. Compared to them, women in civilian context appear in a lower number. On one hand, the analysis of these women could lead to new data on the process of Romanization, regarding the presence of indigenous names or the clothing style visible on tombstones. Also, the presence of various social groups could reveal differences between the two parts of the settlement complex, the canabae and the civil town. But on the other hand, microhistorical research could show new aspects regarding the structure of Roman society, including Roman-Barbarian relations. There are some outstanding examples, like a 10-year-old wife, the forgotten, but distinguished wife of a slave, or the only known priestess of Brigetio.

As the pilot project of a wider, systematic analysis of women in the province of Pannonia, this presentation tries to show the possibilities, what results could be carried out by examining this forgotten group of Roman provincial society.

Paweł Szymański (Faculty of Archaeology, University of Warsaw, Poland), Iwona Lewoc (Terra Desolata Foundation, Warsaw, Poland)

Enamelled Roman Brooch from the Czarna Struga in Puszcza Borecka – short report

In 2023 archaeological reconnaissance of the north-eastern part of Puszcza Borecka was launched as a joint initiative of the Terra Desolata Foundation and the Faculty of Archaeology, University of Warsaw. During the research, several uncharted archaeological sites were registered. At archaeological site Szwałk 18, which was initially defined as a settlement of the West Balt milieu peoples, bronze enamelled Roman brooch type I.32 according to K. Exner was found. It was most likely manufactured in the Rhine workshops. This is the second find of this type in the Masurian Lakeland and probably the fourth in the Baltic lands.

The presentation includes the portrayal of the artifact, the circumstances of its uncovering, as well as its position within said site. We will also analyse the location of the brooch in the context of finds known from the Balt milieu and European areas.

Agnieszka Tomas (Faculty of Archaeology, University of Warsaw, Poland)

Novae and the Barbarians. Tracing Encounters Through Material Culture

From the cultural and socio-economic point of view, the place where Novae was founded had a transit character between the La Téne culture and Hellenistic heritage, which was well communicated in the inscribed boundary stones containing an expression inter Moesos et Thraces. The fortress was located in specific and unfavourable transitional areas within the frontier zone, between the non-provincial lands north of the Danube and the Roman Empire. Nevertheless, together with Durostorum, it became one of the most stable and longest-standing Roman military centers along the Lower Danube.

The presence of non-Roman ethnos in Novae during the first three centuries from its foundation is difficult to trace. In the period of conquest and consolidation of the lower Danubian provinces the military bases were isles of romanitas expressed in many spheres of life including material culture, religious acts and official language. After the 3rd-century crisis this picture began to change in the last decades of the 4th century onwards. A closer look at several interesting finds from this period will illustrate the nature of these changes and the possibility of their assessment by modern scholars.