Organisers: Agnieszka Tomas (Faculty of Archaeology, University of Warsaw), Tomasz Dziurdzik (Faculty of Archaeology, University of Warsaw), Emil Jęczmienowski (Faculty of Archaeology, University of Warsaw), Justyna Dworniak-Jarych (Institute of Archaeology, University of Lodz)

Session language: English

Date: 24.03.2021

Whether in legionary fortresses or auxiliary forts, the headquarters were the principal area of the military base and an ideological equivalent of the civilian forums in the cities. As the heart of the camp, this central building was placed at the crossing of two main streets (groma). The major part of the headquarters was occupied by a vast internal courtyard, which was by no means an empty space – but a place to express loyalty to the emperor and his family, military discipline, and those elements of Roman religiosity which defined devotion to the authorities and the romanitas. A monumental hall (basilica principiorum), the administrative rooms, but first of all — the temple of standards (aedes principiorum) were the most important spaces within the military base, but still their role and internal arrangement remains not fully understood.

The complex function, as well as the appearance, and the sculptural and epigraphic setting of the principia buildings was a subject of various publications, but still needs more comprehensive studies. In the late 1980s Tadeusz Sarnowski made a first attempt to present the hypothetical arrangement of the headquarters building in Novae and in the early 1990s Oliver Stoll did an analogical effort with regard to the military bases in the Upper German-Raetian limes. On the other hand, the subject of the military religion and pietas with its ideological compound has been studied by various scholars from Arthur Darby Nock (1952) to Christian Schmidt Heidenreich (2013). However, many problems remain still unsolved: Were the military clubs located in the principia? What was the function of the entrance halls in some auxiliary forts? How and why principia evolved during the Principate? What happened with the function and role of the headquarters buildings in Late Antiquity? How were they repurposed in former military bases? How can we trace those problems and changes: in epigraphic evidence, archaeological discoveries or in the nature of small finds?

This session will focus on several topics related to the principia buildings, amongst them:

– Architecture and decoration;

– Epigraphic and sculptural arrangement;

– Multifunctionality and role in Roman military administration and religion;

– Small finds from the headquarters;

– Principia in Late Antiquity.

The session is organised as part of the ‘In medio castrorum. Sculptural and epigraphic landscape of the central part of the legionary fortress at Novae’ research project of the National Science Centre of Poland (ref. no. UMO-2016/21/B/HS3/00030 – OPUS 11)

The session schedule is available here.

Speakers and papers with abstracts:

1. Ștefana Cristea (National Museum of Banat Timișoara, Romania)

The Emperor’s Numen Cult as Civil Religion in the 3rd century AD

This paper adopt J.J. Rousseau’s definition of civil religion, in order to observe to what extent the “positive dogmas” defined by him can be highlighted in the religions of the 3rd century in the Roman Dacia. He believes that the state needed a religion that would help people to be good citizens, to ensures social unity, a religion that will bring together high moral values inspired by a divine force and the love for lows and in the same time a religion in which the divine force and the source of political power are interlinked in such a way that for the citizens “to serve the state means to serve the tutelary deity” and “to violate the laws means impiety”. At the end of the 2nd century and especially in the 3rd century, expressions such as d.n.m.e. (devotus Numini Maiestatique eius) become quite common in the inscriptions dedicated to the emperors. This did not mean that the emperor was a deity per se, but that he had a Numen, a divine power, and the inscriptions were not erected to the emperor, but for the emperor. The main focus of this paper is to argue to what extend this aspect of the imperial worship can be considered a civil religion and a test of loyalty in Roman Dacia. The inscriptions containing this locution were discovered in Roman Dacia both in the military environment, in Principia, in the sacred area where inscriptions were dedicated to both the emperor and the protective deities of the military unit, and in the civilian environment at Drobeta, Tibiscum, Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa, Micia, Mehadia, Romula etc.

The spread of this aspect of the imperial cult was easily achieved with the help of the coins. Being represented as equals, as companions, suggests that emperors and gods belong to the same realm and consequently, a certain god’s power was the emperor’s power as well (e.g. Gordian III and Serapis), the moral values encouraged by the worship of this god became the moral values encouraged also by the emperor.

2. George Cupcea (National Museum for Transylvania’s History, Cluj-Napoca, Romania)

Altar and Statue to Mars in the principia of Apulum

During the rescue excavations conducted in 2010-2011, inside principia of the legionary fortress of Apulum, Dacia, a series of epigraphic monuments were discovered. Some of them attest a large variety of officers, most of them centurions. The general report and plans were published by the excavation team in 2015.

During the archaeological investigations many other monuments were discovered, most of them in their original position.

One of the monuments is an altar of particular interest. It was discovered inside the room adjacent to the aedes to the south (inv. no. R11107) and is currently displayed in the Principia Open Air Museum, Alba-Iulia, Romania. It is particularly well preserved, finely decorated (on both sides, we see round shields with a round central boss, in front of a crossed duo of a sword (spatha) and a spear (hasta), made of limestone and bearing a most interesting inscription, concerning a very particular officer of the legionary cavalry.

3. Alexandru Flutur (National Museum of Banat Timișoara, Romania)

Aspects of Religious Rituals in the Trajanic principia

All the spaces pertaining to the headquarters building’s area can be related to certain religious rituals, which took place at a certain moment. Some were unique, some were repetitive. On locus gromae, the sacred axes of the fortress were drawn. In the courtyard animal sacrifices were performed. Here and within the basilica many monuments related to the imperial cult had been found. The weapons and armamentaria equipment were also consecrated. The aedes held the strongest sacredness, where the eagle (aquila), the standards and the imagines of the emperors were kept.

Although there is much information concerning the religious deeds performed inside the principia, the reconstitution of the rituals is still difficult. Mircea Eliade giving the example of a 1966 burial ritual of the Nevada Indians, shows that the rites and especially the religious ideology they imply, can no longer be “recovered” on the basis of remnants founded by archaeologists. The magic and religious beliefs from the Roman Empire are better documented as compared with those from prehistory that come only from archaeological excavations. We have ample literary sources from the Greco-Roman period regarding religion or eloquent artistic representations. Valuable information on the official feasts of the Roman army comes from Feriale Duranum. Also from Dura Europos comes the famous fresco of Iulius Terentius depicting the incense sacrifice before the statues of the Palmyrene gods. Nevertheless, knowledge on the magic and religious rituals of the Roman army can only be partial.

Archaeological excavations in the Trajanic period principia from Berzobis (Berzovia, Caraș-Severin County, Romania) brought to light a curse tablet (tabella defixionum). It was found in the implant hole of a post of the first wooden basilica (timber phase I). The inscription in Greek letters (BAΛΓI) has not been elucidated. The placing of the tablet was deliberate but the meaning of this magic ritual is hard to clarify.

4. Florin-Gheorghe Fodorean (Department of Ancient History and Archaeology, Babeș-Bolyai University, Romania)

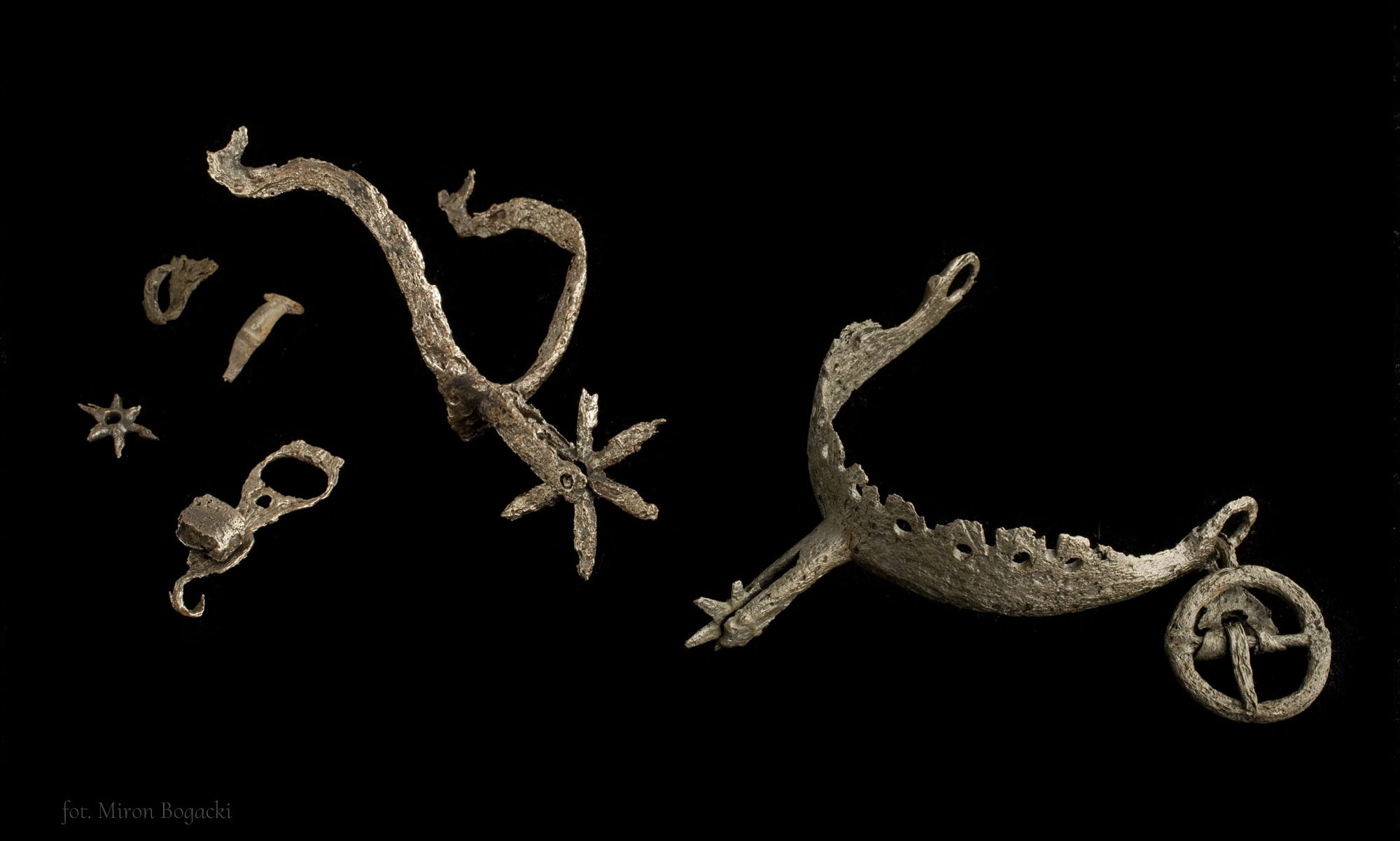

The Military Equipment and the Weapons Discovered in the principia of the Legionary Fortress at Potaissa (Turda, Romania)

A total of 40 Roman weapons have been recovered from the headquarters building at Potaissa. These finds are common types, utilized by the legions all throughout the Imperial period: three spearheads, seven spear sockets, four pilum heads, six pilum catapultarium heads, seven arrowheads, two pugiones, a discus pertaining to a dagger handle, two gladii, and eight stimuli.

Evidently, these finds are more frequent in the Principia than the ones discovered in the legionary baths or the barracks situated in the praetentura sinistra. Alongside weapons, a series of Roman military equipment elements were uncovered in the headquarters building at Potaissa. The finds have been divided in the following categories:

I. Belt appliques (54 finds), with four subcategories:

a. square shaped belt appliques with fretwork decor;

b. belt appliques with various shapes and designs;

c. belt appliques with flat discus;

d. belt appliques with domed discus;

II. Belt buckles;

III. Belt rings (the so-called „Ringschnallencingulum”);

IV. Cingulum buttons;

V. Loricae clasps (five loricae squamatae clasps and seven loricae segmentatae clasps);

VI. Scabbard lockets;

VII. Snaps (six bronze snaps, one ivory snap and one horn snap);

VIII. Pendants;

IX. Lorica squamata chainmail;

X. Chest plate armor;

XI. Belt ends;

XII. Helmet strengtheners;

XIII. Helmet handles;

XIV. Belt distributors;

XV. Utere felix belts;

XVI. Tent pegs (”Zelthaken”, paxillus tentorii);

XVII. Unidentifiable objects.

5. Cristian Gazdac (Institute of Archaeology Cluj-Napoca, Romanian Academy of Science, Romania)

Hiding or Dropping – the Meaning of Coin Hoards/Deposits Found in the Principia Complex

The possibility of using large database on coin hoards – such as the Coin Hoards of the Roman Empire (Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford) – together with applied case studies may allow us to establish general and specific patterns on the coin assemblies discovered in the Principia of the military forts throughout the Roman Empire.

The paper will analyse the number and composition of hoards found in the principia together with the archaeological context and historical background in order to determine the meaning of such numismatic evidence in the military headquarters. The analysis will be carried out on an area stretching from Britannia to the Balkans, on the Roman limes, as well as the internal forts. Principia from forts such as Novae, Potaissa, Carnuntum, Lauriacum, Intercissa, etc. are excellent cases that throw a new light on the interpretation of what the term ‘hoard’ could mean.

During the archaeological investigations many other monuments were discovered, most of them in their original position.

One of the monuments is an altar of particular interest. It was discovered inside the room adjacent to the aedes to the south (inv. no. R11107) and is currently displayed in the Principia Open Air Museum, Alba-Iulia, Romania. It is particularly well preserved, finely decorated (on both sides, we see round shields with a round central boss, in front of a crossed duo of a sword (spatha) and a spear (hasta), made of limestone and bearing a most interesting inscription, concerning a very particular officer of the legionary cavalry.

6. Emil Jęczmienowski (Faculty of Archaeology, University of Warsaw, Poland)

Headquaters Before the Disaster. Maintenance of the Lower Danubian principia During the Reign of Valens.

This paper deals with the subject of maintenance, architecture and function of the principia buildings inside the forts along the Lower Danubian ripa, especially during the reign of Valens (AD 364–378). The archaeological data concerning different kinds of activities in the area of principia – both the ones from the Principate era and those built during Diocletian-Constantine period – are not very abundant for the period under discussion but still allow us to draw some general conclusions that during Valens’ reign headquarters along the Lower Danubian ripa were still highly regarded. Even if their function somehow changed in comparison to the period of Principate – which is well reflected in their architecture – and some of them were already abandoned.

7. Kamil Kopij (Institute of Archaeology, Jagiellonian University in Cracow, Poland), Adam Pilch (Institute of Archaeology, Jagiellonian University in Cracow, Poland), Monika Drab (Institute of Archaeology, Jagiellonian University in Cracow, Poland), Szymon Popławski (Institute of Archaeology, Jagiellonian University in Cracow, Poland), Kaja Głomb (Institute of Archaeology, Jagiellonian University in Cracow, Poland)

One, Two, Three! Can Everybody Hear Me? Can Everybody See Me? – Acoustics and Proxemics of Military contiones

In our paper we present our project One, two, three! Can everybody hear me? Can everybody see me? – Acoustics and proxemics of Roman contiones. The project focuses on acoustic and proxemic analysis of selected speaking platforms from which Romans have spoken publicly in both civilian and military context. Our main goal is to determine the maximum number of recipients that were able to hear speeches intelligibly as well as to see gestures of an orator.

Since most known military contiones took place in camps where the troops resided and the speaking platform (pulpitum) was placed within the principia our primary concern are these structures of three camps: Carnuntum, Novae and Dajaniya. Additionally, we plan to analyse the campus of Carnuntum as a possible place of speaking to soldiers. This will enable us to compare results obtained through analysis of three very different structures, divided geography, chronology and in terms of materials from which they were built.

The analyses will be conducted based on 3D virtual reconstructions of the structures taking into account acoustic properties of the materials from which they were build. Using Catt-acoustic software we will run simulations in order to establish Speech Transmission Indexes (STIs) for different background noise levels (between 36dBA and 55dBA). At the same time we will establish maximal visibility of three different classes of rhetoric gestures based on results of experiments we conducted.

Based on the results of acoustic and proxemic simulations (the areas of audibility and visibility) we will estimate crowd sizes using two different methods based on modern observations of the behaviour of crowds. As a result we:

- will estimate the number of people that could intelligibly hear a speaker and see his gestures for all case studies,

- will establish whether all gathered soldiers were able to hear the speech intelligibly as well as see the gestures of the speaker or not.

8. Lyudmila Kovalevskaya (The State Museum-Preserve Tauric Chersonese, Sevastopol, Crimea)

Rare and Little-Known Amphora Types of the 1st century AD from the principia at Novae

In 2011-2012, two pits filled with rubbish of the 1st century AD were excavated in the territory of the headquarters building at Novae. Among different categories of material, the filling included fragments of 140-160 amphorae. Most vessels were typologically identified as production of major ceramic workshops situated on the islands of Kos and Rhodes, in Heraclea Pontica, and in the territory of Syria and Palestina. Some amphorae are difficult to classify. They can be divided into two groups:

- amphorae of little-known, uncommon types;

- amphorae of extremely rare types that at the moment seem not to have parallels neither in the Mediterranean nor in the Pontic region.

The first group contains following types:

– «Diverses amhpores greques»;

– «Bojović-554» (Pseudo-Gauloise);

– «Kelemen Type 8» – similis;

– «Kelemen Type 11» – similis.

The second group contains following types:

– amphorae of very large dimensions morphologically close to big vessels of the type «Brindisi amphora» / «Dressel 26»;

– sharp bottom amphorae of quite large dimensions;

– sharp bottom amphorae of very small dimensions.

It may be assumed that two former types were morphological imitation and continuation of earlier traditional shapes of amphorae originating from ceramic centers in Aegean and Pontic regions.

Due to the fact that the pits are close assemblages with reliable dating, the containers under discussion can provide a chronological benchmark for future studies. Further examination of these types, most notably clarification of their origin, will make it possible to expand geographical range of trade relations of the Roman legionary camp at Novae.

9. Martin Lemke (Antiquity of Southeastern Europe Research Centre, University of Warsaw, Poland)

A Place to Live, a Place to Command: the Relationship of principia and praetorium in Roman Army Camps and the Problems Related to Finding the Latter in Novae/ Bulgaria

There was never any serious doubt regarding the placement of the principia of Novae, or any other legionary camp of the principate for that matter, temporary facilities excluded. The headquarters building of the legio I Italica lies in the general centre of the camp, just south of the via principalis. This offers three possible locations for the living and working space of the unit’s commander, the legionary legate, commonly known under the name praetorium. With the western flank across the principia being occupied by the legionary bathhouse, the land plots south and east of them are likely candidates, but a building extra muros has also been brought into the discussion. In my presentation I will sum up the status quaestionis on this matter.

10. Felix Marcu (National Museum for Transylvania’s History, Cluj-Napoca, Romania), George Cupcea (National Museum for Transylvania’s History, Cluj-Napoca, Romania), Dan Augustin Deac (History and Art County Museum, Zalău, Romania)

Tetrapylon and the Entrance in the principia of Certiae, Dacia Porolissensis

In 2018, a research project conducted by the most relevant archaeological institutions in Transylvania, The Museums in Cluj and Zalău, the University of Cluj, in close partnership with the University in Bayreuth, Germany, attempted to solve the puzzle of a structure identified in the centre of the auxiliary fort of Certiae, the village of Brusturi, Sălaj County, after magnetometry investigations executed by a Dutch-Romanian team in the late nineties. Interpreted and published by one of the authors of this presentation and member of the excavation team, the structure was considered to be a tetrapylon, a multi-arch entrance in the principia, and sacred monument which decorated and marked the intersection of the two main roads of the fort, locus gromae. We are now after the third campaign and we can argue that the magnetometry results were confirmed, even if there still are lots of questions to be answered.

11. Nemanja Mrđić (National Institute of Archaeology, Belgrade, Project Viminacium, Serbia), Milica Marjanović (National Institute of Archaeology, Belgrade, Serbia)

Viminacium – principia of the VII Claudia Legion

Viminacium and its legionary fortress are the most important military stronghold in the Upper Moesia. Systematic geophysical surveys have been conducted since 2001 and since 2016 parts of the ramparts closing the area between West and North gates have been in progress. Principia was more than obvious choice for the next step in research. As a parts of legionary fortress is still in private ownership and this was a limiting factor.

Research had to be therefore focused on public areas and excavation begun in south east corner of the principia. Proton magnetometer provided us with outer walls of the building and some details within. Ground penetrating radar was used in the north east section giving detailed information on state of preservation and further distribution of rooms.

Excavations conducted during 2020 covered part of the forum, tribunal, portico and 8 rooms. Heating and water supply systems were also excavated. Multiple building phases are identified and correspond to the chronology of the castrum previously established. One coin hoard discovered in room 3 dates potential disaster into the years after 330 AD, but no final destruction phase of the building and castrum is yet defined. Question remains whether Viminacium fortress was abandoned or destroyed.

12. Ioan Carol Opriș (Department of Ancient History, Archaeology and Art History, University of Bucharest, Romania), Alexandru Rațiu (The National History Museum of Romania, Bucharest, Romania)

The Late Roman Headquarters from Capidava

The Late Roman principia (the headquarters building) belonging to the cavalry unit garrisoned in the 4th century at Capidava (province of Scythia, nowadays in Constanța County, Romania) was exhaustively excavated in the last decade (seasons 2013-2019). During the Dominate, only cavalry units have been attested in the Danubian garrison at Capidava. A troop of equites scutarii, possibly the same as vexillatio Capidavensium, was mentioned by two votive altars. According to Notitia Dignitatum (Or. XXXIX, 13), in the early 4th century it was replaced by another cavalry unit, cuneus equitum Solensium.

The late Roman headquarters building from Capidava, with its apsis facing south-east, was already visible in the 1950s in the southern part of the fort (in so-called Sector VII). This was possible following the large-scale excavations of the upper layers containing stratiotai sunken dwellings that have taken place on the terrace parallel to the river.

The edifice itself was built in late 3rd – early 4th century. It represents a typical 25m by 19m structure with a peristyle courtyard (6.80 by 10m), a transversal nave (basilica) and was provided with a southern side ended in an apsis, hosting the sacellum/ aedes. It has good analogies upstream the Danube, at Sexaginta Prista and Iatrus, both in the neighboring province of Moesia Secunda. Both architectural remains and archaeological material strongly argued that the headquarters superposed 2nd-3rd century structures, resembling the barracks of the cohors quingenaria garrisoned at that time in the castellum at Capidava. During the 6th century the ensemble has turned into a civilian habitation and to this purpose was subdivided into smaller rooms by adding walls of stone and adobe bricks bonded with clay. This conversion is virtually identic to the one observed in the case of the nearby largest public building inside the castellum – the 4th century horreum. Likewise, 9th-11th century sunken dwellings, using building stone from inferior layers and disturbing the coherence of those important buildings in ruin, were erected during the so-called Middle Byzantine final period of the site. Our paper will focus the most important chronological observations and conclusions regarding the functional aspects resulted from the systematic excavation, and will also contain a preliminary comparative analysis with similar headquarters of its time.

13. Mirko Rašić (Department of Archaeology, University of Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina), Tomasz Dziurdzik (Faculty of Archaeology, University of Warsaw, Poland)

A Possible Early Stone principia at Gračine – Combining a Reinterpretation of Old Excavations with New Research

The Roman fort at Gračine (Humac in Ljubuški community, Bosnia and Herzegovina – in older literature identified with ancient Bigeste) represents an interesting scientific problem. Although the central part of the site, with the remains of two buildings, has been excavated in the late 70s, the results were never fully published – and the excavators badly misinterpreted the functions of the uncovered remains. In fact, the unfinished state of the research even led some to believe that the site was not a Roman fort at all. Only starting in 2015 the site was the subject of renewed research: the reinterpretation of the old excavations, as well as non-invasive research of the eastern part of the site, followed by a verification excavation of some of the detected geophysical anomalies. Thanks to this, the remains of two barrack blocks have been securely identified. The research thus allowed a final confirmation that the site is indeed a Roman fort, closing this part of the scientific discussion concerning Gračine. However, the results mean that a total reinterpretation of the remains uncovered in the 70s is needed. We propose that the preserved architectural remains should be interpreted as the principia and praetorium of the fort, in a layout strongly resembling the early, Augustan examples from other regions of the Empire – but here constructed in stone. This suggests an exceptionally early dating for the earliest phase of the fort, which could have interesting, far-reaching implications for the military history of Dalmatia – as well as for the history of development of Roman permanent military installations. The paper will also present the further research steps which will be needed to verify and confirm our theory.

14. Tadeusz Sarnowski †, Agnieszka Tomas (Faculty of Archaeology, University of Warsaw, Poland)

Donum aquilae. A Golden Gift by primus pilus to Hercules and the Eagles of the 1st Italic Legion

In 2012 and 2013 the earth works during the construction of the Archaeological Park in Novae have brought to light a number of inscribed monuments. One of them was an octagonal monument unearthed in the central part of the legionary fortress, on the courtyard of the headquarters building (principia). The limestone monument funded in AD 187 by primus pilus of the 1st Italic legion bears a special inscription informing about the military cult of Hercules and the eagles as well as about the decorations which were donated after a vow. The analysis of the text and the execution of the monument gives an interesting insight into the religious activity of the most important non-governing officers in the legion known as primi ordines, as well as the sculptural decoration of the headquarters building.

15. Călin Timoc (National Museum of Banat, Timisoara, Romania)

Architectural Evolution of the Principia of the Great Fort from Tibiscum (Jupa). New Perspectives on Older Data

The principia-building from Tibiscum big fort is one of the most excavated archaeological units from Tibiscum. The first researches are attested in the late 60ties of the last century when a big quantity of architectural marble stones (a good part with inscriptions) were collected from the central, inside area of the castrum. Most of the findings are preserved in the National Museum of Banat – Timisoara, brought by professor Marius Moga, the first Romanian specialist who was digging there. These first excavations look more like a rescue excavation done in communist times because some agriculture projects planned on the fields from Jupa, close to the Timis (Tibiscus) River. The research was accomplished in years: 1985-1986, with the publication in 1990 of the final report and other small trenches released in 1994, when the ruins of the principia-building get in the restoration works prepared for public visit. Doina Benea who published in the monography of Tibiscum the evolution of the Roman forts explains also the general plan of the principia and offers the basic chronological landmarks. Rethinking the findings, especially the architectural objects we can now explain in a new perspective how this headquarter structure of the garrison from Tibiscum developed and how it looked in its period of glory.

16. Domagoj Tončinić (Department of Archaeology, University of Zagreb, Croatia), Mirjana Sander (Department of Archaeology, University of Zagreb, Croatia)

In Search of Lost principia from Roman Legionary Fortress Tilurium

The roman legionary fortress Tilurium is situated in the hinterland of Salona, the capital of the Roman province of Dalmatia. It was built on a plateau overlooking the right bank of the Cetina River (Hippus), on a dominating and strategic position controlling the surrounding fields and plateaus, as well as the crossing over the Cetina in the area of the town of Trilj (Pons Tiluri). From 1997, the Roman legionary fortress becomes for the first time part of an archaeological research project. Since then, contours of fortress architecture have emerged to see the light of day. On the extreme western end the remains of a massive western rampart have remained preserved above ground to this day. Excavations were carried out on a building lying parallel to the western rampart and on a cistern in the northwestern part of the fortress, with remains of a canal that probably carried water to the center of the fortress. The excavation in the southeast part of the former fortress revealed a segment of the south rampart and the remains of military barracks (centuriae) oriented east-west. In addition west of them further military barracks, oriented north-south and laying adjacent to the previous, were revealed. The remains of a floor mosaic were found in the central part of the fortress. A fragment of the central field depicting the rear of a bull remained preserved. The location in the center of the fortress, together with other data, suggests that the mosaic may have been part of the principia, but due to objective circumstances it has not been possible to confirm this so far by archaeological excavations. The intention of this paper is to draw attention to the numerous data collected during more than 20 years of research in Tilurium that speak about the position and appearance of the principia.

Registration for the scientific session: “Principia. Roman Military Headquarters from Archaeological Perspective. Thaddeo Sarnowski – Proffesori Praestantissimo in Memoriam”, March 24th 2021

* All fields are required